the ascendent genre

Contents:

Welcome

DOC NYC: Raphaela Neihausen

Interview: Julia Bacha

Interview: Vaishali Sinha

Legend: Cara Mertes

Welcome to the second issue of Doxx Magazine.

This set of content features filmmakers who screened new work at DOC NYC, as well as conversations with two other essential festival figures-- Executive Director Raphaela Neihausen, and Leading Light Award recipient, Cara Mertes.

Cara called documentary the “ascendent genre.” I hope you feel a sense of reverence for the two films in this issue, which I believe command such a description. Julia Bacha’s Naila and the Uprising, about one Palestinian woman’s non-violent contributions to the 1980s Intifada movement, feels like a proverb on peace and justice. And Vaishali Sinha’s Ask the Sexpert, which is a charming and important documentary about a renowned sexologist in Mumbai, is an affirmation of the strange, wonderful, and sometimes unfortunate experiences of having a human body. I believe these films capture some of the breadth of possibility with documentary, as well as qualities that are intrinsic to exceptional work in the genre.

“Women have always been an incredibly strong part of the documentary world, although it will tend to be men, specifically white men, who receive a lot of the accolades. But women have been there since the beginning.”

-Cara Mertes

We’re growing here at Doxx Magazine, and I’m committed to maintaining progress at a steady rate. Slow growth is the strongest, so content won’t be bursting at the cyber seams anytime soon. Amidst the media maelstrom, I want to offer you a manageable amount of reading. I hope each interview is consumed in a single serving, perhaps on your commute, or while avoiding your boss in a bathroom stall. I hope the material inspires reflection and awe.

While you’re here, don’t forget to sign up to stay in the Doxx Loop. And please spread the word! I wouldn’t want you or any of your pals to miss out on our fantastic future. If you have suggestions, ideas, want to write for the magazine, or wish to express any kind of documentary dream, please email info@doxxmagazine.com.

More soon.

Rachel

First, an introduction to DOC NYC with Raphaela Neihausen, who is the festival’s Executive Director. She answered questions over email about the inception of the event, and how it’s come to grow and flourish.

What’s the story of how DOC NYC began? How did it grow from idea to now?

Since 2005, Thom Powers (my spouse) and I had been overseeing a weekly documentary series at Manhattan’s IFC Center called Stranger Than Fiction. In 2010, IFC Center’s General Manager John Vanco asked us to start an annual documentary film festival, which we agreed to do. The festival started off quite modestly in terms of size, but by its fourth year, had grown to be the largest documentary festival in America. This year was our eighth edition and we hosted 250+ films and events, with 300+ special guests.

How has the festival changed since its beginning?

For one - we actually have a staff! In the first year, there were a handful of us working in a basement with Thom and I overseeing all programming, budgeting, marketing, hospitality and development. Now we have a talented team that works alongside us and helps push the boundaries of what the festival can accomplish.

We have also significantly grown our non-film programming. One highlight is our eight-day series of panels/conversations called “DOC NYC PRO”. Each day begins with a Morning Manifesto by a key person in the field and then continues with panels with key filmmakers and industry, associated with daily themes that vary from commerce to craft. Another highlight is our “Only In New York” program where we select filmmakers with works-in-progress to meet with key industry professionals in a series of rotating roundtables.

The most significant difference is that we’ve been able to create a true community that includes seasoned filmmakers to newbies, from both NYC and abroad. Festival guests and pass holders converge to spend eight days networking over daily breakfasts and happy hours in our DOC NYC PRO lounge. We have many repeat visitors who have been attending for years.

What is it about documentaries that continues holding your attention?

In this day of frantic news cycles and shrinking attention spans, documentaries have become the most thoughtful way to explore any given issue at hand. They serve as long form journalism, presented in an artistic thoughtful way that engages the viewer. Even when the films are “short” in length, there is an incredible amount of thought and time that goes into creating them.

Another exciting aspect is the diversity of perspectives. With the accessibility of technology, there are more filmmakers and viewpoints than there have ever been before. I’m also pleased to observe the level of craft continuing to evolve year over year. Documentary film is an incredibly dynamic and rewarding medium.

Have submissions (volume and content) from female-directors changed over the last 7 years?

We haven’t tracked gender in our submissions, but I’m proud to say that our content has hovered between 40-50%.

How do you want the festival to fit in the documentary community and beyond?

I would love the festival to continue doing what it’s doing well - highlighting strong filmmaker work, fostering a documentary community, serving as a focal point for both filmmakers and industry to meet and check-in on the state of documentary. In recent years, we have been seeing more and more international visitors - filmmakers, industry and even audience members. I would love to further build on DOC NYC’s reputation as a destination festival worth the trip.

Where is the festival headed?

Stick around and find out!

Sparked by the bombing of her childhood home, and fueled by unjust imprisonment and the exile of her husband, Naila’s political ideals become essential to her identity. Rather than choose between family and community, she instead recognizes the inextricability of self-determination for Palestine, Arab women, and herself.

As men of the occupation opposition are deported en masse, women step into leadership roles, bringing innovative, peaceful tactics to the movement. A surreptitious network of daughters, wives, and sisters secretly distribute leaflets in loaves of pita and bags of spinach, and buttress the inseparability of women’s rights and national sovereignty. The nonviolent precepts of community education and resistance weave together a vibrant, steadfast mobilization.

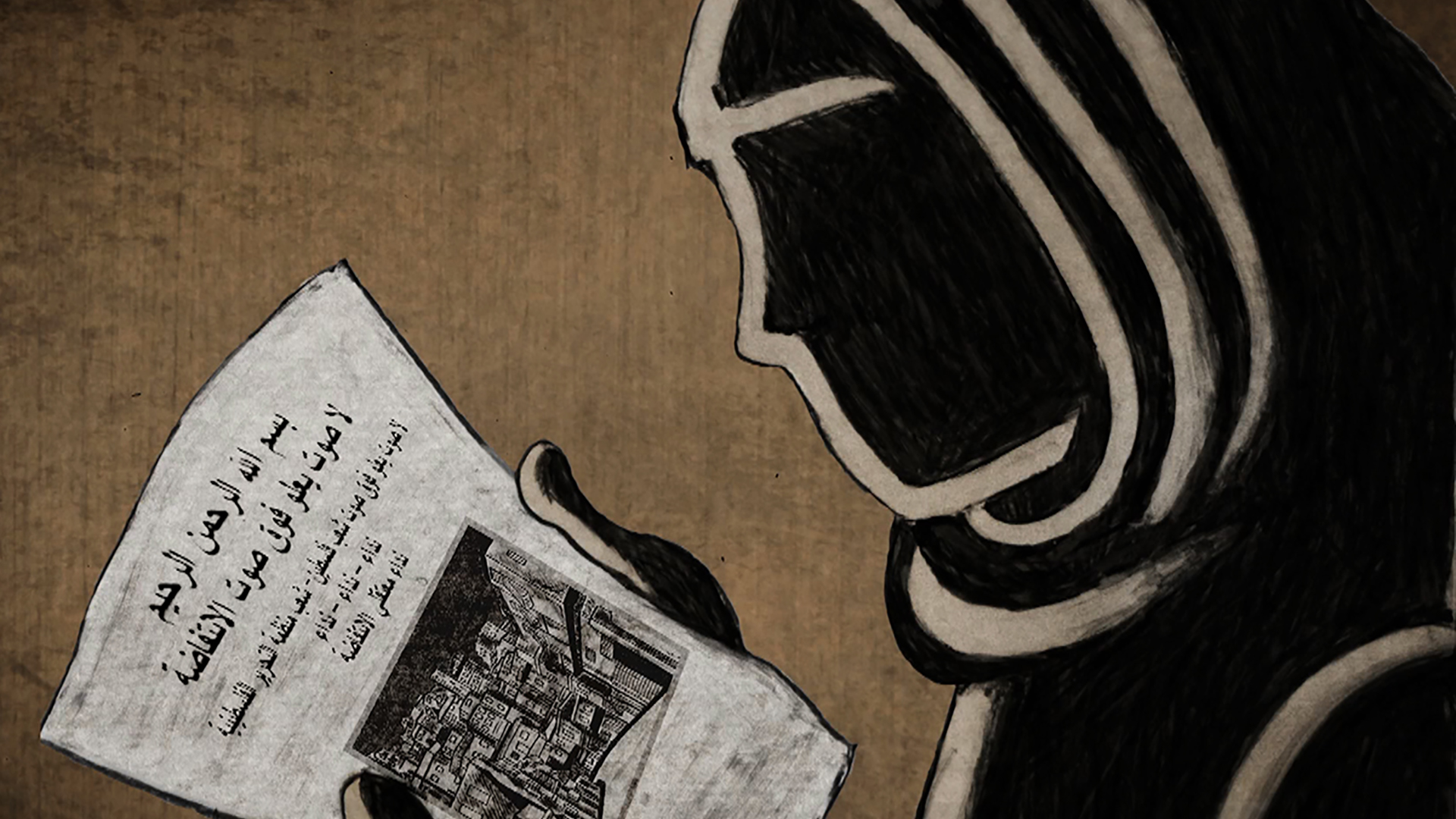

In addition to traditional interviews and archival footage, Bacha employs phantasmagoric animation to fill in historic context. Its fable-like aesthetic and featureless faces invite the viewer to imagine yourself as a player in this ancient strife. The timeless theme of liberation echoes a parable, both Biblical and Quranic.

Director Julia Bacha on films for change,and going beyond the festival circuit

Julia Bacha didn’t predict the last 14 years of making films to support the peaceful movement in Palestine and Israel. After co-writing and editing Control Room (2004), about the inner-workings of the Arab satellite channel, Al Jazeera, the Brazilian-born filmmaker assumed she would turn her attention elsewhere. But a chance encounter and more exposure to regional dynamics revealed a trove of everyday champions in the shadows, dust-covered histories, and a local urgency to fill under-documented truths.

Bacha is the creative director at Just Vision, an organization that supports, amplifies, and galvanizes grassroots, nonviolent efforts of Palestinians and Israelis working to end the occupation. Through digital media, documentary, and direct programming, their diverse scope inspires action on the global stage and among rooftop audiences in the communities where they film.

Bacha’s most recent work, Naila and the Uprising, chronicles the tumultuous life and resilience of Palestinian Intifada organizer, Naila Ayesh, as her personal experiences and political efforts dovetail in the 1980s.

Naila in Demonstration, as seen in Naila and the Uprising, Directed by Julia Bacha. Image Courtesy of Mahfouz Abu Turk.

Can you talk about the process of coming to the story of Naila, and what it was like getting to know her, and gaining her trust?

I’ve been working together with a team at the nonprofit Just Vision for 14 years in Israel and Palestine. This is the fourth documentary film that we made, all of which focuse on the civil society leaders that are using nonviolent resistance to end the occupation. And in the process of all these years, all the activists on the ground that we’ve been documenting have been urging us to talk about the first Intifada, and to really uncover the history of what’s in place, particularly in terms of the women’s leadership, which has been hidden from the sight from most of the international community, and Palestinians themselves. The younger generation has not heard what happened during that time. So we started a research process about 4 years ago. We interviewed dozens of women and men on the ground who were part of the uprising. And gradually we were really drawn to Naila’s particular story because of the arc of what she experience encompasses so much of what it feels and looks like when women join a resistance movement. We really wanted to make sure that the full scope of what Naila and her colleagues did there, as well as the aftermath of what happened during the negotiations phase, became part of how we understand Israel and Palestine today.

How did you approach her about starting the project? What was her reaction to being featured?

Because we’ve been working for so many years on the ground, we know a lot of the activists. Our producer, Rula Salameh, was a very young woman—she was 15 years old—during the Intifada, and was very active herself. So, she knew Naila, and she knew most of the women we interviewed already. There wasn’t a lot of work needed in terms of gaining trust because the trust was already there. Unlike some teams that parachute in and then out of conflict zones to make films, we have teams that are in the conflict—they live there, and their families are there. So the storytelling is very much embedded with the production team itself.

Your films Budrus and Naila and the Uprising emphasize the women who have been at the vanguard of Palestinian resistance. Why do you focus on, and return to the women who have been involved in these movements?

“when women are actively engaged in protest movements, and when there is a focus in gender equality as part of the ideology of these movements, the protests tend to lead to more democratic and peaceful societies in the long term.”

I think that, similarly to what happens in other parts of the world, women tend to be either written out of the history of the protest movements, or sometimes not written into them in the first place. But in fact, women tend to really form backbones of sustaining movements because of the role they play in their communities and in their families. And erasing them really does a disservice to all of us, because there’s plenty of anecdotes and social science research that prove that when women are actively engaged in protest movements, and when there is a focus in gender equality as part of the ideology of these movements, the protests tend to lead to more democratic and peaceful societies in the long term. So what we’re doing by erasing women from these protests movements is really preventing us from building communities that can be peaceful in the long term, and that can avoid conflict in the long term. So, writing women into the history is a really critical first step if we want to build a future that is pluralistic and inclusive.

There are conflicts happening all over the world at any given time. What is it about the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, and Middle Eastern politics, that continues to hold your attention?

The truth is that I did not grow up thinking that I would be dedicating my life to supporting the peaceful movement in Israel and Palestine. I grew up in Brazil, and it was a coincidence how I ended up there in the first place 14 years ago. What has kept me there, over the years, and one film after another, is the sense that we’re making a difference. If I felt that we were telling the stories and it wasn’t having any impact on how people were talking about Israel and Palestine, or how people were acting in relationship to Israel and Palestine, I would probably have moved on. I have lots of interest, like anybody else, and there are a lot of things that I’m passionate about, and that I would love to make films about. But, I do make movies to make change, and the team at Just Vision that we have created over all these years, makes it possible for the films to work beyond the film festival circuit, beyond the broadcast date, and deep into communities. And I really love that. That’s what keeps me going.

What happened 14 years ago that you first encountered the Israel/Palestine conflict?

The first film that I ever worked on is called Control Room, and it’s about the Arab satellite channel Al Jazeera, and how they covered the war in Iraq in 2003. And when that film came out in the U.S, a human rights activist saw it in the theaters, and called me and said that she wanted me to work with her on a film she was doing in Jerusalem. My first reaction was no way. I didn’t want to get involved in that! I felt there was too much attention being given to Israel and Palestine, and there were other stories that were invisible, and that needed more attention. I didn’t understand the dynamics yet, and what was happening on the ground. So the first time I went there, I was astounded to meet incredible Palestinian and incredible Israelis who were risking their lives and their livelihoods in order to build a peaceful future for both societies. People were really incorporated and acted on values that I think most people around the world also share, and they were invisible. So I became very passionate about making them visible.

First Intifada Demonstration, as seen in Naila and the Uprising, Directed by Julia Bacha. Image Courtesy of Mahfouz Abu Turk.

Can you talk about—especially now in this era of manic and fake news—what you see as the role of documentary film as a strategy for fostering productive conversations about violent and divisive issues?

Documentaries hold a special place on the continuum of art and journalism. And I think it’s a really wonderful place that human beings respond a lot to. There’s something in our psyche that makes us attuned to narratives and stories. There’s plenty of scientific research that says if you want to change someone’s mind, don’t tell them facts, tell them a story. Documentaries are very good at that—we tell stories. What we do differently from fiction films or other forms of art that involve storytelling, is that we have a journalistic ethic as well. So, we feel that it’s very important to tell the truth. We combine storytelling with the truth, and that’s really powerful because the human brain responds to story, and with true stories, you can help people have a better grasp of what the world looks like around them. I think the more documentaries become a popular medium, and the more people can see documentaries, the better off we will be for building a global community and building empathy for each other.

I was really struck by the animations in Naila and the Uprising. It made the film feel like there was a universal moral to it. Can you share what your intentions were with the animations, and how you developed that style with the animator?

It’s my first time working with animation, and I’m absolutely in love with it. I was afraid of using animation—I didn’t know how it was going to combine with the archival footage, and whether it would feel complementary with all the different styles that were going to have to be brought together. We were very lucky to find the team of animators that we found. We did an open call a couple years ago, where we provided a scene of the film, and asked animators from around the world to suggest styles of animation to tell that particular story. And the moment I saw Sharron Mirsky and Dominique Doktor’s work, I knew right away they were the ones I wanted to work with. It was clear. I just looked at it and it clicked—nothing else would work. We talked about what were the key themes that we needed to have animated, and what were the most important moments. And it was a really exciting, creative process going from the rough drawings and doing the designs for the different characters, up to adding the final color—it was a really thrilling experience.

What was it about their style that you knew the fit was right?

Woman and Leaflet, still from animated sequence in Naila and the Uprising, Directed by Julia Bacha. Image Courtesy of Just Vision.

It was the dreamy nature of it. It allowed you the put yourself in those scenes. It gave you just enough information to understand what’s happening, but not too much that it separated you from the images. I felt that that was what we needed to make people identify with the stories we were showing on screen.

Naila and the Uprising takes place chronologically before Budrus. Did documenting these moments out of linear historical order inform how you see the politics of the conflict?

At first we wanted to look at activism in contemporary terms, and then based on feedback from the activists, it became very clear that unless we corrected history, it would be very hard to move forward with a new narrative for Israel and Palestine. And the first intifada became the key historical time that needed a corrective. And that’s what made us decide to go there.

Your films span rural and urban communities. Can you talk about unification and the separation of Palestinian countryside vs cities, and how the politics spans those different settings?

I think in different historical times it means different things. Currently, unfortunately, the West Bank is divided in 3 different areas by Israel—area A, B, and C. And Palestinians in these different areas have limited ability to move between the different areas. They’re frequently separated from their families by the wall that cuts across the West Bank and divides communities. Villages tend to be in Area C, which is completely controlled by the Israeli military. People there live on full-on occupied areas. Area A is very urban, and has heavily populated areas. Those cities have some degree of self-management—Palestinians perform the daily functions of sweeping the streets and running the hospitals etc, but they can’t leave the city. They’re prisoners inside their little enclave, which really reminds you of apartheid South Africa. So that’s the biggest challenge right now for Palestinians to unite—there are so many artificial divisions that have been created—that were created in the Post-Oslo period, as a result of Oslo, in fact, because of poor management of the negotiations, and because women were excluded. Now we’re in the situation we’re in.

What are the dynamics you experienced of being a female filmmaker in the Middle East?

The big advantage is that you have greater access to places that are more female spaces. And the disadvantage is that you are subjected to the Israeli army, which uses sexual harassment and all those things.

What did you do in situations when you were harassed by Israeli military?

There’s not much to do to mitigate it. The main thing is that they’re trying to use interrogation opportunities for intelligence gathering. You just shut your mouth and don’t say anything. But it’s very hard. I’m completely traumatized by it. But it’s very small compared to what Palestinians go through.

Have you received resistance to your films from Israeli government officials or citizens who might see them as anti-Israel?

Yeah, the issue is highly controversial, and divisive. We’ve been incredibly lucky—and that’s the result of the fact that we work with both Palestinians and Israelis at the grassroots level—working with people who are basically asking for democratic pluralism. It’s harder to attack our storylines because they’re so inclusive of the future, that attacking them goes against values that people like to say they agree with. In terms of whether the Israeli government is happy with the films we’re making, they’re obviously not.

What are some other specific examples where you’ve seen your films serving to bring Israelis and Palestinians together?

Budrus was used a lot by Israeli activist groups as a recruiting tool for more Israelis to join in resistance activities. We saw a very clear link between the film Budrus and the film My Neighbourhood, which was about a resistance movement in Sheikh Jarrah, the neighborhood where we have an office in Jerusalem. And that movement was heavily attended by Israeli activists. And, part of the recruiting strategies that they use was they were doing rooftop screenings in people’s buildings across Jerusalem and Tel Aviv of Budrus. They would show the film and would say ‘by the way, there’s a movement just like that happening just ten minutes from here. Do you want to go there next Friday?’

I was really struck by the female Israeli soldier in Budrus —we see her on the ground expressing these reservations about using force, especially with Palestinian women. She was such an interesting character because she was right on the intersection of many different social dynamics. What was it like talking with her?

Our Israeli producer did the interview with her in Hebrew. She was very clear that she wasn’t regretful about anything that she did. I think her main point was that if she were on their side, she would be doing exactly what they did. She completely understood what was going on, but felt that she had a duty. She can’t quite see how she gets out of that position, but she was very clear eyed about how just the cause of the population of Budrus was.

I just kept thinking she represents the quagmire that the region is in. People on both sides might see the perspective of the other side, but they might still be stuck in one camp.

I think there are different levels of support in different communities to take a stand. I think for her to take a stand would be in opposition to the mainstream way of behaving, and she wouldn’t have any support. And that would be very isolating. I think people are able to take stances that are more challenging to the accepted behaviors when there’s some degree of support. That’s why movements can grow so fast when they reach a tipping point. The growth can be very very slow at first, and feel like it’s not going anywhere. But as soon as you reach a certain amount of people that allow hundreds of thousands of others to feel like there is now community to take that stance, then that growth becomes exponential.

What’s Naila’s attitude toward the future?

It’s a very difficult reality on the ground. But overall, you see individuals who are activists in their nature and in their blood. I think there’s a strong commitment and belief that we’re going to keep fighting, and eventually we will get our independence.

Who are you favorite or most influential female documentary filmmakers?

I love Sarah Polley and her film The Stories We Tell. That’s definitely my #1. She’s an extraordinary artist.

Interspersed with writing, Dr. Watsa’s house operates as an open-door counseling practice, “like a train station” for individuals and couples seeking emotional and physical advice. His clients seem to speak with no reservations at all, which, given the delicacy of topics discussed, marks Dr. Watsa as a genuine guide for the human condition.

Surely Dr. Watsa’s age influences his approachability, as well as his celebrity, which appears most fervent among selfie-snapping Millennials. The ripple effect of sex education programs in schools--facilitated by a Watsa-inspired brigade of young teachers-- underscores a generation that is breaking taboos, and demanding cultural shifts.

Virtually unfazed by challenges presented by a crusading moralist, or by his own family’s concerns for his well-being, it’s Dr. Watsa’s attitude that makes this film so charming. When asked if he enjoys his work, he replies, “yeah, why not?”

As her character balances elderly nonchalance with unwavering dedication, Sinha maneuvers between a delightful individual and tender reflection on society as a complex whole, and confirms that there are always more questions to ask.

Director Vaishali Sinha on the infinite intrigue of sex

With Ask the Sexpert, Director Vaishali Sinha wanted to “get back to basics.” Her most recent film in a growing body of work on matters of the human body is an intimate portrait of India’s preeminent sexologist, Dr. Mahinder Watsa. Through Dr. Watsa, Sinha asserts that the best way to talk about sex--that primal and absurd act humans seem destined to misunderstand--is with humor. Mixing and blurring with the solemnity that invariably complicates the comedy, the film is as essential as it is playful.

From his Mumbai home, the 90 year-old Dr. Watsa, a former gynecologist, writes a regular newspaper advice column, in which he answers queries about anything and everything sex-related.While most of the questioners are men, and frequently concern male anxiety, Dr. Watsa always steers the answers to empower women.Perched at his computer, we watch his two index fingers skim across the keyboard, gently typing out answers to dozens of daily questions. Things like “is it better to wear two condoms than one?” and “is it okay to use a mascara tube for masturbation?” filter through his blunt honesty and wry wit, and offer the refrain that sex--and all the questions, anxieties, and desires that it entails-- is normal.

Courtesy of Ask the Sexpert

What was Dr. Watsa like as a film subject?

The first time I met him in 2013, I filmed him for 2 or 3 weeks, and afterwards, he said, “great! I think you have everything you need now.” And I was like, “oh boy.” Every time I returned, and every time I would finish my production trip, he would have me over for a goodbye, like a ‘have a good life back in NY, we hope to see the film soon!’ And then the next year, I was back. He was always gracious. He has an open door policy-- he always has people coming and going. It’s like a train station. I think I was also one of those people, initially. He’s always happy to talk to young people, young or old, about this field of sexuality. He’s always like, “sure, come on it!” he just didn’t realize that I would be stay quite as long as I did.

Some people can wax eloquence. I could just sit there and listen to him talk. I could sense something very tangible and interesting going on. I had the gut intuition that I needed to stay with it. Also, he was just really fun. He doesn’t say a lot. I would speak more than him, making up for pauses and blurting and blabbing, and he would come in with his zingers. He’s very measured. He just chooses to think about his answers. It was interesting to be with him because of the world he was opening up for me.

How did you first learn about him?

I grew up in Mumbai, but I left for New York in 2004, and in 2005, the column launched. Even though I went back every year, I never picked up the Mumbai Mirror. I had no idea there was this column that was revolutionary in certain urban cities of India, including Mumbai. This has basically been the staple diet for many generations of Indians for about 10 years now.

“The underlying intention was women’s empowerment and sex education, so I wanted to make a film about sex through character study.”

What was your driving intention with making this film?

I wanted to make a film about sex, essentially, because I make films about sexuality and reproductive health. The underlying intention was women’s empowerment and sex education, so I wanted to make a film about sex through character study. I wanted to know what are the ways in which Indians talk about sex. Because when I was growing up, other than with my friends, there was nowhere to discuss these things. So I thought a sex therapist or a counselor would be my window into that world. I sat in my little Brooklyn apartment scribbling up a script for a documentary where I would find this person who would have clients coming to him—I knew it would be a man, because that’s the more likely person in this profession. In my search, I very quickly came across Dr. Watsa, and it became more than what I had dreamed of.

How has Dr. Watsa responded to the film?

After I first showed it to him a few months ago, and I called him and asked what he thought. He first said, “Well, it takes a while for one to absorb a film about oneself.” That’s all he had to say. He also didn’t think the whole film would be on him, and I was like, “what?! I filmed you for four years!” It was really funny. And then he said, “I can see why it’s popular abroad. I don’t think, though, that people in India will like it.” I had already had one young well known filmmaker who had seen it early on, and was completely in love with it, and I knew how people in India would see this film. I just couldn’t wait for him to be in a roomful of people watching it with him, and for him to realize just how much people love it. And recently in India, he specifically told me, “you know, I told you I didn’t know if people in India would like it, and I was wrong.”

Dr. Watsa has been sexual health advocate for many decades. Did he talk about how his aging has shifted his readership, his clients, and how they relate to him?

The fact that he’s 90 makes it a safe way to talk about sex; he’s very nonthreatening because of his age. I don’t think he thinks of himself like that. It’s funny—other people who have known him or have worked with him, when they were younger they all remember him as old. He’s been old for a long time. He tells his kids, “there’s nothing to retire from when someone’s reaching out to you and they’re searching for someone they vibe with.” so I don’t think he thinks of himself as old, necessarily.

The film is character driven, and it’s also sociological—how did you balance the micro and the macro perspective, and how did they inform each other?

That was always an interesting thing. This was my first portrait documentary, and that was its own challenge. My first film Made in India had a three act structure, but there was no such narrative structure with Ask the Sexpert. It was really more that I was interested in the character a lot, and I was interested in wherever his work was going to take me as a journey.

And, because my subject was communicating with real, multi-dimensional people, with real lives of their own, I could no longer just make a film about just this one person. It had to be about these other people. That balance was very important to me, so I worked very hard at working to weave in those voices, while keeping it a character driven film.

Courtesy of Ask the Sexpert

What do you hope your many audiences get out of the film?

I hope, at the very least, people leave the film feeling like they have a tool or some way to discuss sex and sexuality with their partners, or their children, or whomever. I want it to open up conversations and dialogues. I hope it encourages parents to think of the value of talking to their kids openly about sex, consent, equality—and how it will serve the interests of their kids. Also, for men, hopefully it will alleviate some of their anxiety to see other men go through performance issues, and then to hopefully not just focus on themselves, because that leads to toxic masculinity. Hopefully it will spur us to be a little more thoughtful with our partners and our loved ones.

Through the making of the film, my mom and I talked about sex for the first time. It’s funny to say that. But I would shoot in Mumbai, and my mom would stay up at the end of my shoot day, waiting with a cup of tea. And she’d ask, “so, who came to Dr. Watsa today?” It was just really fun to be able to talk to my mom about it. During post production, we had a couple interns, and they all told me in some way or the other that they were able to have conversations with their parents about sex because of this film.

Your first feature Made in India-- about surrogacy-- is also about how we value, talk about, and use bodies. What is it that ties together your two films as a body of work?

I’m interested in sexuality, and sexual rights. Reproductive rights is a part of that for me. Part of everything I do is about agency and choice and exploring body politics, especially growing up in a country—and I think relevant in the U.S as well—where women’s bodies are controlled. With Made in India, I thought it was really interesting that women were entering this practice in a culture where otherwise selling your body for money or body parts for money would be looked down upon. There was something happening there that was about choice, women’s sexuality, regulation of our bodies, and Ask the Sexpert is also kind of along those same lines. I really wanted to get back to the basics.

Courtesy of Ask the Sexpert

Was there an intentional pivot turning from Made in India, which is about a complex international dynamic, to Ask the Sexpert, which is contained within Indian society?

For me, Made in India is also about India. It was about watching Americans go to India, but ultimately, those who have the most at stake were the women. In that way, the interest wasn’t such a great departure. Sex is a global, universal experience. I really thought that this film has the potential of striking a chord globally. I knew going into India that there’s a lot of taboo about talking about sex, so I thought that would help us really think about the issues at home and here in the U.S as well.

How do you see yourself fitting into that narrative of dismantling taboos around sex? Why is that important to you?

When I make films, I just want to make something I’d like to watch. And I wanted to watch something about sex that I had never seen before-- a film that would show everyday Indian people, who are not so different from everybody else. So in doing that, in normalizing us, we would then be progressing the conversation on equality and rights.

What is the story of how you became a filmmaker?

It’s a long winded road. It was never my original intention. Nobody in my family is a filmmaker, and where I grew up, it’s not considered a career. And perhaps isn’t really one here either, especially for documentary filmmakers. I was raised to think science is a safe career, so I studied physics in college. But then once I was out of the system of what was expected of me, things in India were becoming more experimental in terms of career choices, and I decided to branch out and explore. Then I fell into filmmaking through a nonprofit I was working for in Mumbai that used drama and film as a tool to talk about issues. And I quickly realized that film was the part I was most interested in. I wasn’t cut out to be in an administrative job, the part I was cut out for was to explore something more artistic.

Could you share a particularly important filmmaker’s mistake or challenge?

I’m constantly making mistakes. There was a point where I thought I would just learn from my mistakes, but then I keep making them. So I’m like, “is that just my personality?” I’m just getting older, and it’s not going to get better. It makes you so desperate sometimes. I tell my husband, “I think I need a manager or someone, because the mistakes aren’t getting any better.”

Talking about failure and mistakes is kind of like talking about sex—it can feel shameful, but once you open up about it, it feels really good.

I think we should have monthly meetups about failure. It’s so human-- a dark and funny celebration of being human. I was recently at an awards event and all these iconic figures were saying that it never gets better. They were sweating just remembering each time they made a new film and how every time they thought, “this is going to be a big failure. I’m not an artist, I’m a scam artist.” And it’s like “thank god, it’s not just me.” I only have two films, here’s somebody 30 films later and they still feel it.

Who are some favorite or influential female documentary filmmakers?

I really like Kim Longinotto. I remember seeing her earlier films when I was younger in India. I was helping curate a women’s film festival, and I saw so many boxes of films arrive on our doorstep from Women Make Movies. It sounded like such a far-away organization, and years later they became my distributor. Back then, they had all these obscure films in the 90s of really experimental films by many women. They made such an impact on me.

What’s next for you?

I hope to focus on personal relationships, and have a joyful time as a human being because being a filmmaker is just so demanding. Also, I just love making films about sex and sexuality, so I hope to continue that.

Courtesy of Ask the Sexpert

Cara Mertes

Courtesy of the Ford Foundation

Cara Mertes is the director of JustFilms, the Ford Foundation’s creative visual storytelling initiative. She was presented with the Leading Light Award at DOC NYC, which “is given to a mid-career professional who serves documentary outside of being a filmmaker.” Before starting at the Ford Foundation, Cara served as director of the Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program and Fund, and prior to that, as the executive producer of the PBS documentary series, POV.

Her fierce support for and contributions to documentary film is truly heroic.

It was a pleasure to speak with her on the phone.

What was your first job? And how did you get into the nonfiction film world?

I started waitressing at the age of 13 in Kansas. That taught me a lot about providing things to people on time and on budget. It was excellent training for being a producer. I waitressed for about ten years, all the way through college, because I had to pay for it all. The first job I had in the field was as an intern at WNET in New York, which I arranged my final semester of college. I really learned about every aspect of producing and curating at my early days at WNET-- that was probably where I first understood the power of independent film. My job as the curator of Independent Focus covered all forms of media: animation, experimental film, and documentary. So I was curating a lot of work that was short form, long form, coming from all different kinds of artists. I did that for about 5 years. That was an excellent training ground for understanding what has occupied me since then, which is how to support original voices, and how they can reach mainstream audiences with maximum impact.

Over the course of your career of supporting original voices, how have the contributions of women, and how has the documentary community’s support of women, changed?

Women have always been an incredibly strong part of the documentary world, although it will tend to be men, specifically white men, who receive a lot of the accolades. But women have been there since the beginning. Women are most of the creative producers, and many fantastic directors are coming up. Over time, we’re seeing many more women directors and women directors of color. There’s been a concerted effort to develop those voices, and provide opportunities for people who are underrepresented in terms of the stories being told. That has changed a lot of the past 20, 25 years.

Was there singular moment, or has that been a longer transition to make that concerted effort to support more historically marginalized voices?

I think it’s grown over time. The thing I talked about in my DOC NYC acceptance speech that was a pivotal moment for me was the effect of Tongues Untied, which fueled what is now known as the culture wars. There was a lot of resistance to it, but there was also tremendous amount of support from surprising places. You could really see the fault lines of the national discourse, and the challenges we faced in 1989, ‘90, and ‘91. And we’ve seen tremendous advances in diversifying the discourse, and we’ve also obviously seen a lot of backlash and lot of setbacks. But overall, we have a more diverse set of perspectives that are being represented overall in the documentary field. We have a long way to go still. It’s still a white dominated practice, and it’s still a practice of people who can afford it.

I had the great benefit of working for several women in my early days at WNET who expressly mentored other women. And it’s something I’ve tried to do myself when I build a staff or when I build a team. Women mentoring women and increasing those circles of mentorship and those networks is extremely important to building the kind of leadership talent and artistic talent that we’re seeing come up in this community now. I look at it as a common exchange, not necessarily a top down kind of mentorship situation. If we don’t learn from all of the knowledge in the room, you’re leaving a lot on the table.

What projects have had a unique or special impact on you that you’ve contributed to or support?

There is a type of project, and a type of maker, that I find profoundly important to work with, and those are the filmmakers who work over the course of decades on a single project. Their work continues to come back to an exploration of certain questions they’ve set up for themselves. They work across a number of projects or they take a very long time on their projects. These are the most difficult makers to support, especially in the early days because their projects may take 5 or 10 years to see fruition, but I think they’re the most impactful. These are people like Ellen Kuras, Yance Ford, Thomas Allen Harris, Laura Poitras, and James Longley. There are many more I could name. With them, there’s a dedication to a very in depth exploration of social and artistic and creative questions. In other words, they build a career, not just a project.

Why do you believe in documentary? What is it about stories that are true and are about real life that is significant?

I worked with all genres originally. I think I became attracted to the power of nonfiction because of that relationship to the real and the unknown. The form speaks to me about the things that are hidden, underserved, and underrepresented. They’re the underdog stories. I think that in any society, you need a mechanism to lift up those voices, and to bring those voices into a larger conversation about what makes a good society. Nonfiction is an excellent strategy to do that. And it’s powerful. All forms of storytelling rest in the imagination and the ability to imagine new worlds, and nonfiction, because it has a relationship to something that has actually happened, or perspectives that reflect some kind of real condition in the world, has an extra gravity.

Right now, we have this situation where truth itself is under assault across the world, and documentary has a very important role to play. It’s linked to journalism, and fact finding and storytelling, but it has the extra dimension of the imaginary in it, in terms of creative storytelling, and that makes it a very powerful instrument for truth telling in a society that is really desperate for it.

What makes a good story? Is it the maker, or is there something intrinsic to a good nonfiction story?

It combines the power of the imaginary with something that has happened in the real world. And the storyteller is the one who brings their experience and their creativity to it. Hopefully audiences find that. I don’t think a good nonfiction story has to be mainstream. I don’t think it has to have a broad audiences. I think it has to be true to the artist's intention.

“Right now, we have this situation where truth itself is under assault across the world, and documentary has a very important role to play. ”

In this age of fake news, outlandish politics and the watershed reveal of sexual harassment, what else is exciting about the ability of nonfiction now, and for the future?

I think it’s the ascendant genre. We live in a visual age-- it is the most compact, efficient, scaleable form of storytelling. In a global context that is undermining any sense of what’s real and what’s true. So that’s exciting. And I think many people are being drawn to it because of that. It’s an incredibly elastic form-- it absorbs a lot of experimentation. And what I think is going to be exciting about it in the future is what we know about telling stories that have some relationship to the truth or truths--I think we’re going to have to carry those lessons into the immersive storytelling space. We’re going to have even more critical questions to answer in terms of the ethics and impact of storytelling. Immersive storytelling -- if we think onscreen storytelling is powerful-- is exponentially more powerful for humans to experience. I think lessons learned from documentary to date, over the last 100 years, are going to be extremely informative, in terms of how we handle the immersive story world.

Are there risks documentary is vulnerable to given current political climate, combined with the experimental nature that more people are approaching documentary with?

There have always been risks with any kind of visual storytelling from the beginning. There are the extremes, like being used for propaganda, and using the power of this kind of storytelling to promote the kinds of power and corruption we’ve seen take root. Leni Riefenstahl is the example people point to. The ability of this form to carry a message of demagoguery, fascism, or authoritarianism is extremely powerful. Which is why we have a whole study of ethics and accountability of documentary practice. And those two strands have been there since the beginning, and they continue today.